Living Wages and Living Income Worldwide. Update October 2024

WageIndicator Foundation

Amsterdam, October 2024

(latest update if this page: 10 April 2025)

Authors: Martin Guzi, Nii Ashia Amanquarnor, Daniela Ceccon, Martin Kahanec, Paulien Osse, Fiona Dragstra, Kea Tijdens, Nina Holičková

Copyright 2024 by author(s). All rights reserved.

Picture cover page and pictures throughout the report: Ⓒ Paulien Osse

WageIndicator Foundation - www.wageindicator.org

WageIndicator Foundation is a global, non-profit organisation operating in 208 countries. WageIndicator started in 2000 to contribute to a more transparent labour market by publishing easily accessible labour market related information online. We collect, analyse, and share data on minimum wages, salaries, living wages, living income, living tariffs, labour laws, collective agreements, and gig and platform work. Our aim is to enhance labour market transparency for workers, employers, academics, trade unions, and policymakers worldwide. Through its 220 websites, available in 70+ languages, events, newsletters and social media, WageIndicator reaches millions of people yearly.

The authors:

- Martin Guzi is affiliated with the WageIndicator Foundation, Masaryk University, Central European Labour Studies Institute (CELSI) and Institute of Labor Economics (IZA)

- Nii Ashia Amanquarnor, Data scientist, WageIndicator Foundation

- Daniela Ceccon, Director Data, WageIndicator Foundation

- Martin Kahanec, Labour Economist, professor at Central European University in Vienna, and affiliated with University of Economics in Bratislava, Central European Labour Studies Institute (CELSI), the WageIndicator Foundation and Global Labor Organization (GLO)

- Paulien Osse, Co-founder WageIndicator Foundation, Global Lead Living Wages

- Fiona Dragstra, Director, WageIndicator Foundation

- Kea Tijdens Co-founder WageIndicator Foundation

- Nina Holičková, Data analyst, Central European Labour Studies Institute (CELSI)

Corresponding author: Martin Guzi, Masaryk University, Faculty of Economics and Administration, Lipová 41a, 60200 Brno, Czech Republic, Email: martin.guzi@econ.muni.cz or WageIndicator Foundation: office@wageindicator.org

Acknowledgements

Many people contributed to the development of the Cost-of-Living survey, the Living Wage calculations and to this report, i.e. Iftikhar Ahmad, Batorava Market Research Services, Ahshan Ullah Bahar, Huub Bouma, Hien Dong Thi Thuong, Hala Chamaa, Angelica Flores, Guide Erisha Manhando, Carlos Felipe Zavala Gomez, Rogério Junior, Ali and Emin Huseynzade, Hossam Hussein, Shantanu Kishwar, Maarten van Klaveren, Mehr Kalra, Jane Masta, Rahna Medhat, Eyoel Mekonnen, Shriya Methkupally, Knar Khudoyan, Rupa Korde, Nermin Oruc, Irene Eduardo Palma, Luis Eduardo Palma, Giulia Prevedello, Mariana Robin, Gashaw Tesfa, Ernest Tiemeh and special thanks to the hundreds of data collectors around the world.

Bibliographical information

Guzi, M., Amanquarnor, N.A., Ceccon, D., Kahanec, M., Osse, P., Dragstra, F., Tijdens, K.G. & Holičková, N. (2024). Living Wages and Living Income Worldwide. Update October 2024. Amsterdam, WageIndicator Foundation.

WageIndicator Foundation

Mondriaan Tower 17th floor

Amstelplein 36, 1096 BC Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Email office@wageindicator.org

This report and its previous versions build on the original report by Guzi and Kahanec (2019) on measuring Living Wages globally. Since 2019, this report has been updated often, sometimes multiple times a year. Below you find the specific changes that have been made at each update.

2022

In 2022, this report was updated in February and May:

- Guzi, M., Amanquarnor, N., Ceccon, D., Kahanec, M., & Tijdens, K. (2022). Living Wages worldwide, update 2022. Amsterdam, WageIndicator Foundation, February

- Guzi, M., Amanquarnor, N., Ceccon, D., Kahanec, M. & Tijdens, K. (2022). Living Wages worldwide, update 2022. Amsterdam, WageIndicator Foundation, May.

2023 - February

Guzi, M., Amanquarnor, N.A., Ceccon, D., Kahanec, M., Osse, P., & Tijdens, K.G. (2023) Living Wages Worldwide, update February 2023. Amsterdam, WageIndicator Foundation.

In February 2023 the following topics were included:

- Living Income and Living Wage Plus.

- Insight into the role of data collectors

- Latest quarterly data.

2023 - November

Guzi, M., Amanquarnor, N.A., Ceccon, D., Kahanec, M., Osse, P., & Tijdens, K.G. (2023). Living Wages and Living Income Worldwide, update November 2023. Amsterdam, WageIndicator Foundation.

In November 2023 the following topics were included:

- Single income earner as an option in the Family types

- Next to Region - Urban/ Rural now also Peri Urban / Peri - Rural

- Ethical Principles Implementation Living Wages Guidance

- Latest quarterly data, yearly average data, Guidance data

2024 - October

In October 2024 the following topics are included:

- Role of ILO in the Living Wage concept

- Minimum Wage database linked to GPS codes of relevant parts of cities, regions, countries and optional to company locations.

- WageIndicator introduces the ‘Living Tariff’ as a concept

- Additionals on top of the basic basket of goods: (child) care, private car cost

- Inclusion of ‘Adequate Wages’

- Publication of publicly accessible Living Wage estimates in May 2024

Article 23 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms that every individual who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration, ensuring a dignified existence for themselves and their families. The 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set for 2030 and adopted by all UN member states in 2015 add urgency to Living Wage implementation, since paying a Living Wage furthers at least eight out of the 17 SDGs (Van Tulder & Van Mil, 2022; Kingo, n.d.). In addition to these global goals, recent regulatory frameworks, including the European Commission’s 2020 Adequate Minimum Wages Directive, the 2022 Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the 2024 Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDDD) further highlight the importance of fair wage practices and ensuring wages are adequate to at least meet workers’ basic needs. Living wage commitments are an important piece of corporate Human Rights policies, as also recognised by the OECD Due Diligence Guidelines (Balestra, Hirsch & Vaughan-Whitehead, 2023). Along with UN Global Compact’s Forward Faster, where Living Wage is one of the pillars, there is increasing pressure for businesses from investors, consumers, ESG agencies and external bodies, to commit to paying your employees a Living Wage; some have even been cooperating with their suppliers to achieve Living Wages in their supply chains (Mapp, 2020).

A critical step in the global progression of living wage occurred with the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Meeting of Experts on Wage Policies, including living wages, in February 2024, which reached a consensus in March 2024. The conclusions of this meeting reinforced the importance of transparent wage-setting mechanisms grounded in tripartite dialogue and collective bargaining, ensuring that employers, workers, and governments collaboratively establish fair wages. These practices not only secure fair outcomes but also contribute to workplace stability and social equity. Collective bargaining processes play a significant role in reducing wage inequality by establishing negotiated wage floors that prevent wages from falling below essential living standards (Zwysen, 2024). Research suggests that minimum wages supported by social dialogue and bargaining can help wages keep pace with living costs, thus avoiding stagnation and preventing deepening inequality (Zwysen, 2024; Müller 2024).

One of the first studies that aimed to understand the income necessary for basic living standards comes from Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree’s 1901 study, ‘Poverty: A Study of Town Life’. Rowntree's study was groundbreaking for its methodology, as he developed a "poverty line" based on the cost of a "basket of goods" that included essential items for a working-class family to sustain health and basic living conditions. His research sought to identify what level of income was required for a family to afford essential needs, which he categorised as food, shelter, clothing, and other basic necessities. Today, this approach has evolved into a framework that helps determine the minimum income necessary for a decent living standard, guiding most living wage calculations.

Living wage estimates typically cover essential costs such as food, housing, clothing, childcare, transportation, and healthcare, along with a modest allowance for leisure and emergency expenses. Mankiw (2020) observes that living wage calculations generally exclude significant savings for property ownership, debt repayment, retirement, or education, focusing instead on immediate living costs. Though definitions of a living wage vary in wording, they converge on a shared principle: a wage adequate to meet workers' basic needs without requiring government assistance (Gerber, 2017). The list below shows a selection of definitions of a living wage.

- ILO Constitution (1919) and Declarations:

The preamble of the ILO Constitution (1919) called for an urgent improvement in conditions of labour including "the provision of an adequate living wage." This objective was reinforced in the 1944 Declaration of Philadelphia, which supported policies ensuring “a minimum living wage to all employed and in need of such protection.” Although these early statements did not specify criteria for defining a living wage, they described it as a wage “adequate to maintain a reasonable standard of life as understood in the worker’s time and country.” Following the ILO Meeting of Experts on Wage policies, including living wages, in February 2024, the ILO defines the concept of a living wage as “the wage level that is necessary to afford a decent standard of living for workers and their families, taking into account the country circumstances and calculated for the work performed during the normal hours of work”. This estimate is to be calculated in accordance with the ILO’s principles of estimating the living wage, and to be achieved through the wage-setting process in line with ILO principles on wage setting, such as the need for tripartite dialogue and collective bargaining”. (ILO, 2024)

- Mexican Constitution (1917):

The Mexican Constitution of 1917 states that “the general Minimum Wage must be sufficient to satisfy the normal necessities of a head of family in the material, social, and cultural order and to provide for the mandatory education of his children.”

- Brazilian Constitution (1988):

The Brazilian Constitution (1988) stipulates that the national Minimum Wage must be “capable of satisfying their basic living needs and those of their families with housing, food, education, health, leisure, clothing, hygiene, transportation and social security, with periodical adjustments to maintain its purchasing power”.

The Global Living Wage Coalition defines the Living Wage as “a remuneration received for a standard workweek by a worker in a particular place sufficient to afford a decent standard of living for the worker and her or his family. Elements of a decent standard of living include food, water, housing, education, health care, transport, clothing, and other essential needs, including provision for unexpected events”.

The Asia Floor Wage Alliance proposes a wage for garment workers across Asia that would be enough for workers to “be able to provide for themselves and their families’ basic needs – including housing, food, education and healthcare”.

Living Wage Aotearoa New Zealand defines a Living Wage as “the income necessary to provide workers and their families with the basic necessities of life”.

The Living Wage Foundation UK calculates their Living Wage rates on the basis of the Minimum Income Standard (MIS) methodology which focuses on understanding the “income that people need to reach a minimum socially acceptable standard of living in the UK today, based on what members of the public think is needed for an acceptable minimum standard of living. It is calculated by specifying baskets of goods and services required by different types of households to meet these needs and to participate in society”.

A comparative analysis of these definitions reveals a shared foundational principle: a Living Wage universally encompasses the income required to meet the basic needs of workers and their families, thus enabling a dignified standard of living. Notably, the Brazilian Constitution introduces a distinctive approach by mandating periodic adjustments to maintain the purchasing power of the minimum wage, effectively countering inflation and safeguarding the wage’s real value over time. Importantly, the living wage is not (yet) enshrined in legislation as the minimum wage or as social welfare payment. Instead, it should be seen as one of the elements that may inform wage negotiations and improve minimum wages. Or as the ILO Meeting of Experts report notes “promoting incremental progression from minimum wages to living wages”, (ILO, 2024).

WageIndicator welcomes the conceptualisation of living wages and its adjacent principles resulting from the ILO Meeting of Experts in 2024, and follows ILO’s definition and principles in its work on Living Wages: “the wage level that is necessary to afford a decent standard of living for workers and their families, taking into account the country circumstances and calculated for the work performed during the normal hours of work”.

This 2024 report deals with the constituting elements in WageIndicator’s Cost-of-Living data collection, the calculation of WageIndicator’s Living Wages and Living Income, and introduces the concept of ‘Living Tariff’. This report also highlights the newest additions to WageIndicator’s work on Living Wages. For the updates in this report in comparison to previous versions, see Chapter 1.4.

The term Living Wage differs from the terms Minimum Wage and subsistence wage. A Minimum Wage is mandatory, determined through legislation. It should meet an individual’s basic requirements but may imply that a worker relies on government subsidies for additional income. The (statutory) minimum wage may result from social dialogue, collective bargaining, or a governmental or parliamentary decision, but by itself, it does not establish a benchmark that ensures a decent living for its recipients. A subsistence wage is a minimum income that only provides for the bare necessities of life. In contrast, a Living Wage is not mandatory, but paid voluntarily. Whatever the differences, all these concepts attempt to establish a price floor for labour (Mateer, Coppock & O’Roark, 2020).

The importance of a Living Wage lies in that it establishes broader universal standards for a decent living. Besides the standard for Living Income, this includes a ‘normal’ working week (ILO Convention 1, 1919). This concept implies avoiding excessive overtime hours, taking on more than one job, avoiding the risk of becoming a bonded labourer, or to put one’s children to work while forsaking education, for not to be denied basic human rights such as food, clothing, shelter, suffer social depravities, or be able to withstand crises. That being said, paying workers a Living Wage might motivate them to stay with the company, thus reducing recruitment and training costs, and resulting in healthier employees, thus reducing the loss of working hours due to sickness (Gerber, 2017).

The minimum wage, while essential for wage regulation, often falls short of securing a decent living standard for workers due to its limited scope and reliance on baseline subsistence costs rather than actual living expenses (Müller, 2024). The challenge is that statutory minimum wages are typically based on governmental or legislative decisions and may not consider the cost of living in each region. A living wage considers local cost-of-living variations and other basic necessities required for stability, such as housing and healthcare. Studies consistently show that minimum wages tend to lag behind inflation, particularly in high-cost regions, creating a gap between earnings and the income needed to avoid poverty and dependence on public assistance programs (Di Marco, 2023).

Most Living Wage models include the costs of food, rent, transportation, childcare, healthcare, and taxes. Despite the general understanding that a Living Wage makes for ethical and economic contributions, a worldwide standard for calculating Living Wages has still to be set. The present report of October 2024, and its versions of November 2023 (Guzi et al. 2023b), February 2023 (Guzi et al. 2023a), May 2022 (Guzi et al, 2022b) and February 2022 (Guzi et al., 2022a), aim to contribute to a solid foundation for such a global methodological framework. These reports follow a design, already outlined in 2014 to calculate country-level Living Wages for a large number of countries based on these characteristics (Guzi & Kahanec, 2014; Guzi & Kahanec, 2019). Living Wage estimates should be:

- Normatively based;

- Sensitive to national conditions;

- Based on transparent principles and assumptions;

- Easy to update regularly;

- Published online and accessible for everyone.

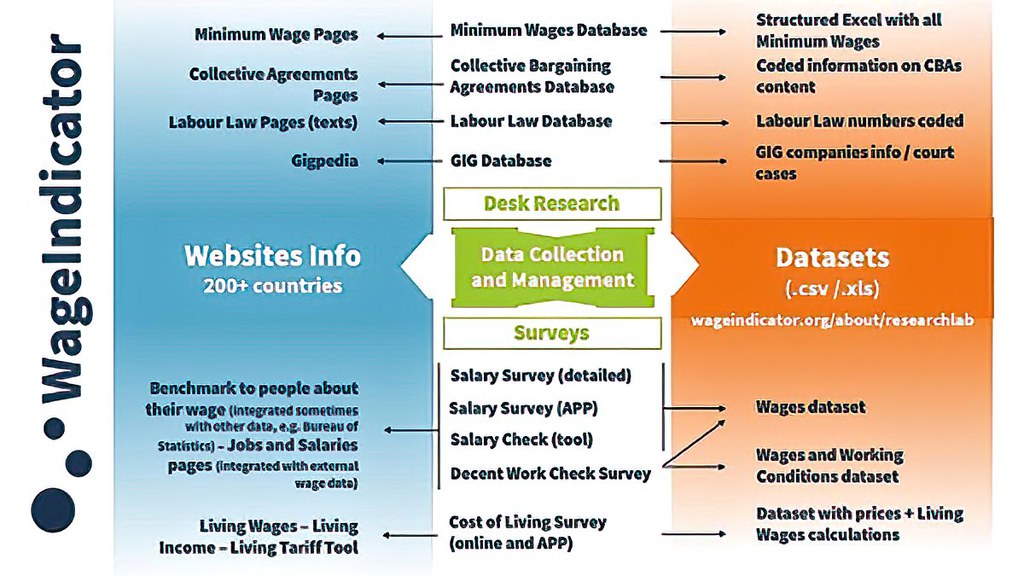

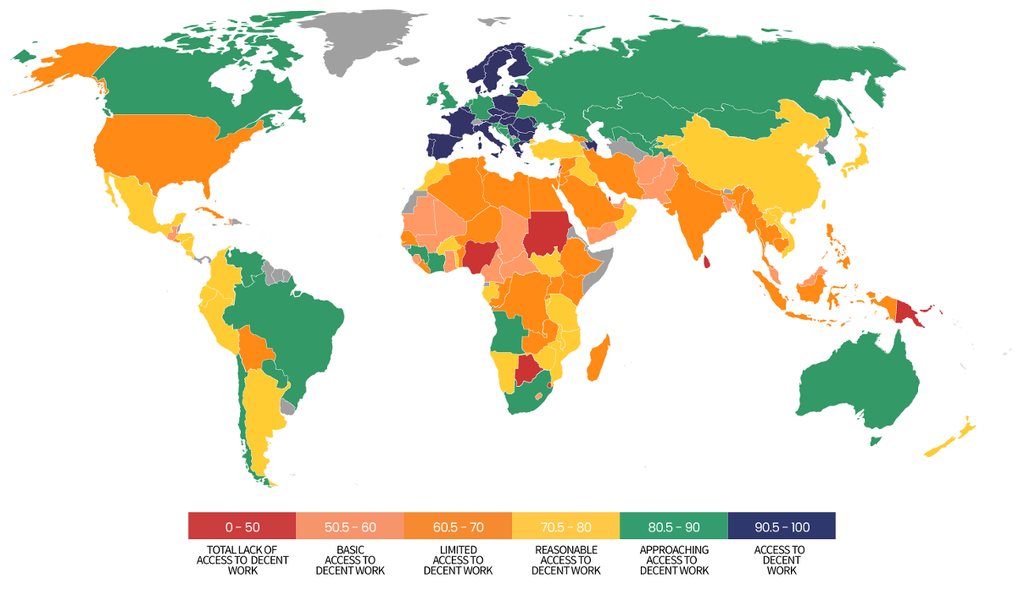

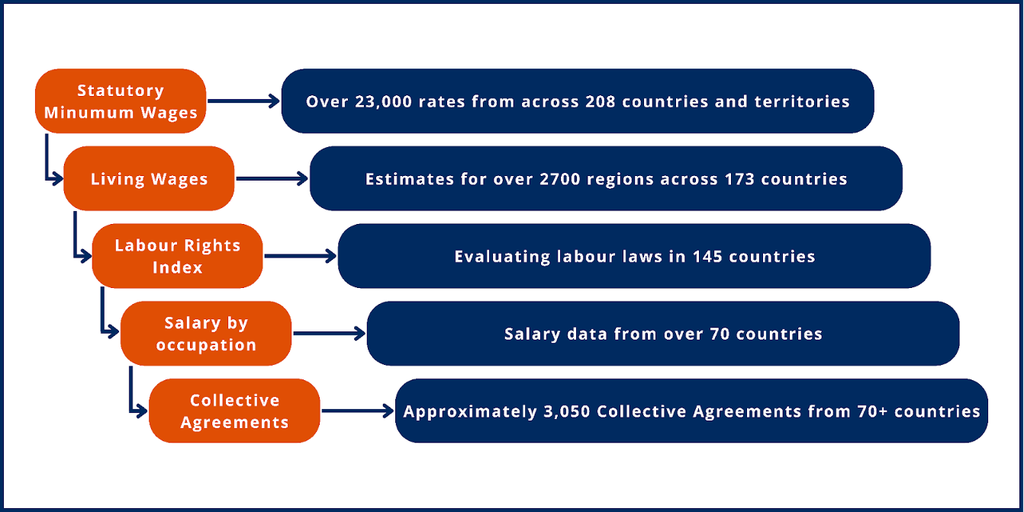

WageIndicator Foundation is a global, independent, non-profit organisation operating in 208 countries across the world that collects, analyses and shares information on Minimum Wages, Salaries, Living Wages, Living Income and Living Tariff, Labour Laws, Collective Agreements and Gig and Platform Work. It aims to improve labour market transparency for workers, employers and policy makers worldwide by providing accessible labour market information worldwide through 220 websites in 70+ national languages (Image 2). In partnership with leading universities and academic institutes across the world, WageIndicator undertakes research on wages, working conditions, labour law compliance, the gig economy, and collective bargaining.

In 2000, WageIndicator launched its first website in the Netherlands. The European websites followed in 2004, and from 2006 onwards began launching websites for countries across the world. As of 2024, WageIndicator hosts websites for 208 countries and territories, as well as a few thematic ones. These websites, along with WageIndicator’s social media channels and events receive millions of visitors annually. The publicly available Living Wage estimates of WageIndicator pages have been downloaded 34,936 times between 1 May - 1 October 2024.

Databases have been central to WageIndicator’s work since its inception. It operates a Living Wage database, a Salary database, a GPS-coded Minimum Wage database, a Labour Law database, and a Collective Agreements database. Data for these is collected through opt-in surveys online, local data collectors, desk research, price monitoring, and national labour law analysis. WageIndicators databases are interlinked through APIs, where useful and possible.

Image 1. The Flow of WageIndicator databases from data collection to publication and datasets

Source: WageIndicator Foundation 2024

WageIndicator team

WageIndicator has offices in Amsterdam (HQ), Bratislava, Brussels, Buenos Aires, Cairo, Dhaka, Cape Town, Guatemala City, Harare, Islamabad, Jakarta, Kinshasa, Maputo, Mexico City, Pune, Sarajevo and Venice. The foundation has a core team of 75 people and some 150 associates - specialists in wages, labour law, industrial relations, data science, statistics - from all over the world. In addition, WageIndicator works with a global network of over 400 data collectors worldwide in addition. On a yearly basis, WageIndicator Foundation offers around 150 internships to students from various universities across the world, including FLAME University, Central European University, Global Labour University, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, University of Namibia and the Eduardo Mondlane University. In 2023 WageIndicator had a total of 185 interns.

Image 2. Map of WageIndicator countries

In October 2013, WageIndicator developed a plan to collect data about the prices of food items. Given the huge numbers of web visitors, it seemed “easy” to post a daily rotating teaser on all web pages asking web visitors for the actual price of a single food item. Once they had entered a price, they were asked to key in the prices of other items in the Cost-of-Living survey. Items asked about the prices of food, housing, drinking water, transport, and clothing and footwear.

It became clear that the online data collection had to be supplemented with 'on the ground' data collection, observing prices in shops and markets as well as asking individuals about their expenditure for certain items. For this purpose WageIndicator established data collection teams in almost all countries, consisting of professional data collectors, complemented by trained interns.

The methodology of the Living Wage data collection and calculation has been described in Guzi and Kahanec (2014, 2017, 2019) and Guzi et al. (2016, 2022a, 2022b, 2023a, 2023b, 2024). This methodology comprises three elements, notably the methodology to identify the basket of goods, the methodology to collect the prices of the goods in the basket, and the methodology of calculating living wage estimates. This is complemented by guidance for implementing Living Wages. The available estimates allow users and stakeholders to share and compare Living Wages across countries and regions based on a harmonised methodology. This methodology facilitates quarterly updating of the database (see chapter 3.1 for further details of the history of the data collection).

💡Good to know: Less than 5% of overall data in October 2024 was collected from web users. Almost all was collected by professional data collectors and trained interns, improving its quality.

Since 2013, the data collection has advanced significantly, evoking the interest of stakeholders in the field of Living Wages. Demands for detailed information about Living Wages beyond country-level arose, challenging the business model underlying the Living Wage data collection. Initially, the data collection was funded from development aid projects and did not include delivery of data to multinational enterprises.

The first multinational client was welcomed in 2018. Since then, WageIndicator has sold its regional Living Wages to a growing number of global clients and multinational enterprises like Unilever and Maersk, many smaller companies with just a few locations, and NGOs like FairWear Foundation, MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières) or SOS Children's Villages International. Globally, trade union partners and researchers also make use of WageIndicator’s living wages, free of charge.

Since 2014, WageIndicator has taken part in the global discussion on Living Wages (see Annex 4). A few recent examples:

- 26 January 2023, WageIndicator presented during a side-session of the World Economic Forum.

- In spring and summer 2023 WageIndicator presented during UN Global Compact meetings in The Netherlands, Switzerland, Brazil, New York and Stockholm.

- WageIndicator joined the panel “Brand due diligence strategies for living wages: Adapting action to context”, during the OECD Garment and Footwear Forum in Paris in February 2024,

- WageIndicator and FLAME University co-hosted the International Conference on Decent Work and Corporate Social Responsibility in the Era of the SDGs from 21 - 23 March, 2024 in Pune, India.

In 2024 WageIndicator and FLAME University organised together with UN Global Compact India an academic conference titled Moving from Minimum Wages towards Living Wages

The Cost-of-Living survey has been updated and improved for the October 2023 and October 2024 release with both newly added questions and improvements to the wording of existing ones. For precise updates, check Annex 2.

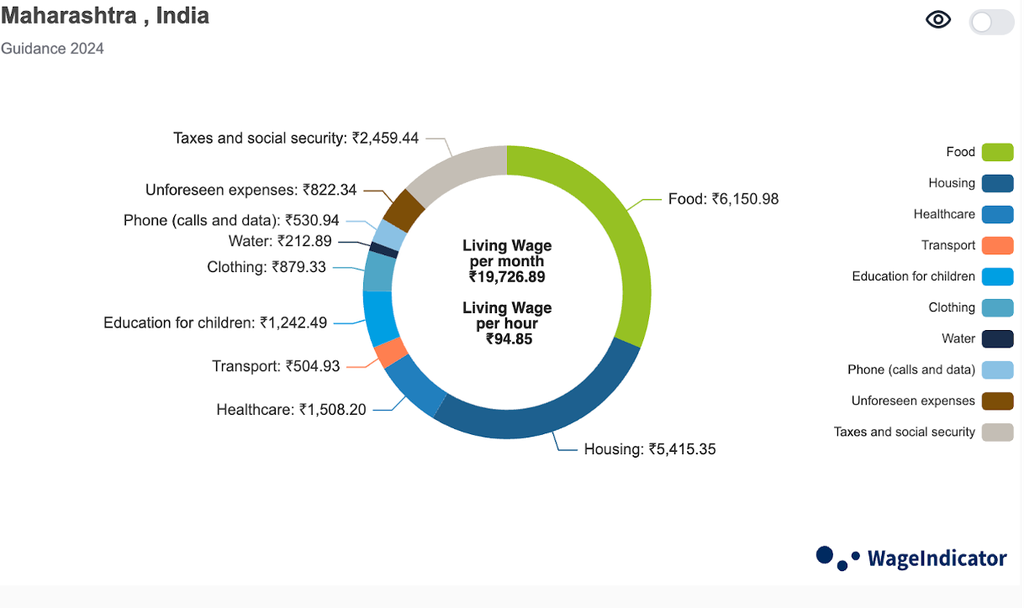

The WageIndicator Living Wage database includes the following since October 2024:

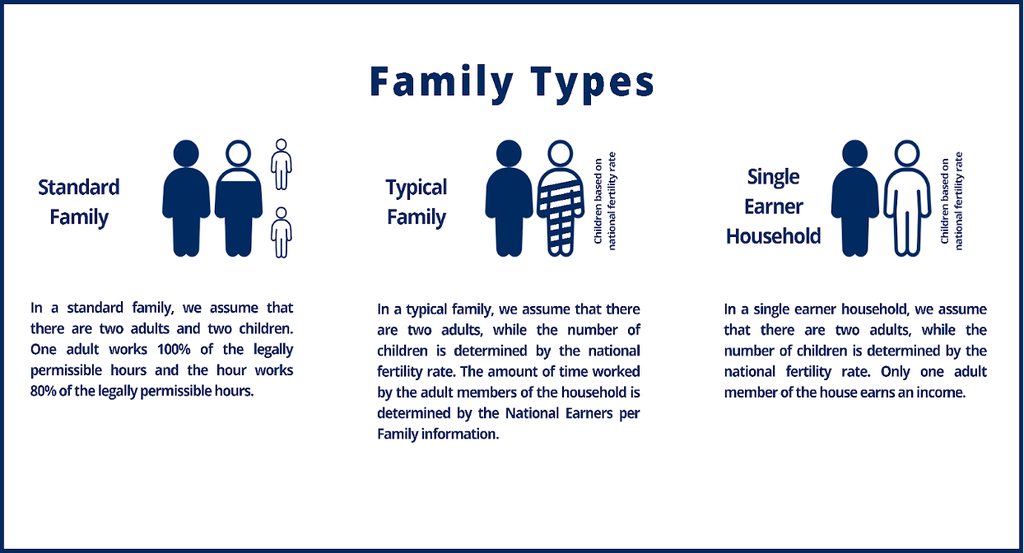

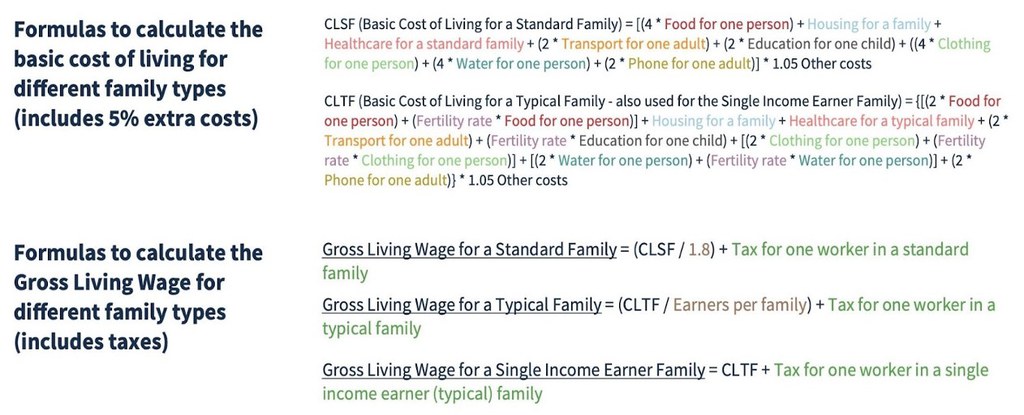

- Next to Standard and Typical Family, WageIndicator also calculates for the ‘Single Income earner’ Family-type. A standard family assumes: two adults, two kids. One of the adults earns 100%. The 100% is seen as the “Living Wage” paid by one employer. The other adult earns 80% by working 4 days. This Living Wage should be paid by another employer. The Typical Family Living Wage assumes two adults, but takes fertility rate in a country and earners per family into account. The Single Income Earner version assumes one adult earns enough for two adults and children according to fertility rate in the country. Lear more about this in Chapter 4.6.

- Beyond regional data, our dataset offers more granularity by providing different estimates for rural, peri-rural, urban and peri-urban areas. A region is seen as an administrative area like a province or county. Learn more in Chapter 6.5.

- The dataset with quarterly updates and yearly averages gets an extra feature: the Living Wage Guidance. On the basis of a set of ethical principles, some countries and some regions are capped to avoid too high spikes over time. The Guidance data can be used for implementation and WageIndicator only publishes the Guidance data. See more about this in Chapter 6.4.

- From July 2024, the delivered dataset includes the Adequate (Minimum) Wages for Europe, calculated using the 60% of the median and the 50% of the average paid wages in the country on the basis of EU SILC data. However, to maintain a global approach, WageIndicator recommends looking at the comparison between Minimum Wages and Living Wages, and to rather use Living Wages that are above the legal Minimum Wages. To assist in this, WageIndicator provides an extra column and a tool to identify the recommended Living Wage per country and region.

- In addition to Living Wage estimates for wage-workers and Living Income estimates for self-employed workers, WageIndicator has released a Living Tariff Tool. The tool is active in Indonesia, India, Kenya, Netherlands and Pakistan. The tool gives insight into the basic tariff for a self-employed person. On top of that the tool allows you to select an occupation popular in the platform industry, like a taxi-driver, rider or translator. The idea behind this is to make clear which items are required to arrive at a basic decent tariff per hour. The Living Tariff includes items like: food, housing, transport, clothes, water, similar to the components from the Living Wage and Living Income. On top of these items cost related items are included for specific occupations. Like a car and petrol for the taxi driver, a bike and helmet for the rider, a laptop and extra internet cost for the online worker. Moreover, the Living Tariff includes components like social security, insurance, pension, and time for administration and training. For some jobs, average waiting time will be included. More about this can be found in Chapter 4 and 6.1.5.

Below, we present an outline of the process resulting in quarterly updated releases of Living Wage data on a global scale. Table 1 gives a summary of this recurring operation. The ensuing chapters elaborate each of the steps, with the choices behind their design and performance. The reader should be aware that this regards work in progress.

Table 1. WageIndicator Living Wage data collection process

|

Recruit |

Recruit & train data collectors from all over the world for data-collection tasks (see Chapter 3) |

| Collect | Assign collection of prices for countries & regions per quarter; manage feedback from data collectors to improve data (see Chapter 3) |

| Maintain | WageIndicator’s IT team maintains and improves the survey |

| Clean and calculate | Clean the data, control for outliers, create scripts and calculate; enrich the data with input from other relevant sources, IMF. Create by October yearly averages and a Guidance dataset (see Chapter 4) |

| Check and present | Quality check and presentation unit; create visuals and sheets for WageIndicator clients (see Chapter 4, 5) |

| Present and provide data | Present the data to clients, calculate salary gaps, do projections, assist in implementation. Run a back office with Question & Answer within 48 hours for the users about the data, and what and how to implement. (see Chapter 5,6,7) |

| Coordinate | Ensure that each quarter, there is enough and timely data. Make sure that the data quality is improved continuously and engage in the global discussion on Living Wages. |

💡Good to know: WageIndicator applies the principle that the data collection in the Cost-of-Living survey and thus the Living Wage calculations take place independently of employers or their organisations, workers or trade unions, or any other stakeholder.

💡Good to know: All data collectors are trained on ethics and adhere to WageIndicator’s Code of Conduct and Safeguarding policies.

This chapter details the ten expenditure categories included in the Living Wage, Living Income and Living Tariff data collection, reflecting the requirements needed for an individual and their family to meet their basic needs. Chapter 3 explains how data about the prices of the items in these categories are collected in the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living survey.

The ten components are:

- Food

- Housing and utilities (water, electricity, heating, garbage collection, routine maintenance, cooking fuel)

- Transport

- Drinking water

- Phone plus internet

- Clothing

- Health (health insurance, personal health, some essential cleaning items)

- Education

- Five percent provision for unexpected events

- Mandatory contributions and taxes on employee’s side (Living Wage), or employees and employers side (Living Income and Living Tariff)

Food, housing and utilities, transport, health, and education are considered essential expenses and are included in all living wage campaigns. Within WageIndicator’s basket of goods, drinking water is treated as a separate category and not included in the food basket, because in some countries it constitutes a significant household expense. Expenses related to clothing and phones are relatively smaller but equally important for maintaining a decent standard of living. The selection of expenditure categories can be influenced by other living wage campaigns and data availability.

In recent years, WageIndicator has established a regular process for calculating changes within these expenditure categories. However, there are many expenses that are difficult to calculate but do enable family members to participate in social and cultural activities. These expenditures are accounted for in the provision for unexpected events. WageIndicator, just as many other Living Wage methodologies, also adds a 5 percent to the final estimate of the cost of living. Finally, taxes and contributions to social security are considered part of the basic essential needs. The final estimate of the living wage is expressed in gross terms, making it comparable to the actual wages paid to employees. For more on Living Income/Tariff, see Chapter 4.

💡Good to know: When we calculate the Living Wage, we account for mandatory contributions and taxes on the employee's side only. When we calculate a Living Income or Living Tariff, we account for mandatory contributions and taxes on the employee's and on the employer's side.

💡Good to know: Living Wage and Living Income/Tariff are based on the categories 1 till 9. Category 10 shows the difference between Living Wage and Living Income/Tariff.

For the ‘Food’ component, we look at the nutritional requirement for good health as proposed by the World Bank (2020) which equals 2,100 calories per person per day (Haughton & Khandker, 2009). The food consumption patterns largely vary across countries, and hence it is important that these differences are addressed in the food basket. The food balance sheets published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO, 2023) include the supply of food commodities available for every country and reflect the potential food consumption basket of an average individual. WageIndicator takes care that an average food basket in a country meets the demand of 2,100 calories and that the food items are sufficiently balanced between the basic food groups, namely vegetables, grains, fruits, dairy, meat, beans, oils, and sweets.

Table 2 shows the 71 items in the food category, for which prices are collected in the Cost-of-Living survey. These items constitute a nutritious food base. As explained in detail in section 4.4, a model diet for each country has been developed on the basis of the FAO food balance sheets and reflecting the varying food consumption patterns and habits of each country. The food items listed in the survey include all food items from the FAO database. WageIndicator groups food items into food groups depending on the major food nutrient category they fall under. Even though prices vary, WageIndicator is interested in the cheapest price in each group. You can view the most recent list changes to the survey in Annex 2.

Table 2: List of food items in the Living Wage Food basket

|

Apples |

Clams, mussels and other molluscs | Melon | Regular cooking oil |

| Aquatic plants (seaweed, lotus, etc.) | Cocoa beans or chocolate | Milk (regular) | Rice (of standard quality) |

| Bananas | Coconuts - including copra | Milk powder | Salt |

| Barley flour | Coffee - whole bean, ground, instant | Mutton, lamb and goat meat | Soybeans |

| Beans - dry | Cream - fresh | Olives | Spinach or other leafy green vegetables |

| Bell pepper or sweet pepper | Dried Fish | Onions | Squid, octopus, cuttlefish |

| Berries | Eggs | Oranges or other citrus | Starchy roots (beet, celeriac, radish) |

| Bottle of water | Freshwater fish - fresh, frozen or canned | Other fish (marine) - fresh, frozen or canned | Sugar (Raw Equivalent) |

| Bovine Meat (beef) | Groundnuts (Shelled Equivalent) | Other poultry meat (duck, goose, turkey) | Sunflower Seed oil |

| Breakfast cereals | Honey | Pasta | Sunflower Seed |

| Bulgur or couscous | Kale | Peach | Sweet Potatoes |

| Butter, Ghee | Lemons, Limes | Peas - dry | Tea |

| Cabbage | Lentils - dry | Pineapples | Tofu |

| Carrot | Local fresh bread - white/brown | Plantains | Tomato |

| Cassava | Local Cheese | Pork meat | Watermelon |

| Cereal flour | Maize (corn) flour | Potato | Yams |

| Chicken | Mango | Prawns, shrimp, crayfish, crabs, lobsters, krill and similar - fresh, frozen or canned | Yogurt |

| Chickpeas or other pulses - dry | Margarine |

Source: WageIndicator Foundation 2024

Image 3. Fish market San Salvador, El Salvador

Source: WageIndicator Foundation, Ⓒ Paulien Osse

Housing costs are very often the largest regular family expenditure. The standards of adequate housing depend on local conditions and therefore WageIndicator takes the cost of privately rented housing as the most realistic available option that is also acceptable in terms of decency. Data collectors are asked to record prices of housing that is not located in a very poor or very rich neighbourhood. The housing should have permanent walls, solid roofs and adequate ventilation. It should have electricity, water, heating - if needed in that area - and sanitary toilet facilities. Individuals (without children) are assumed to rent a studio/ one-bedroom home and households with children are assumed to live in a rented two-bedroom home. Since most of our data collectors are locals, they are aware which areas might be classified under this category. Table 3 shows how participants in the Cost-of-Living survey report the monthly rent, the number of bedrooms and location of their apartments. The collected housing prices are checked for outliers. A typical rent in the lower part of the price distribution (at 25th percentile) and in the middle of the price distribution (50th percentile or median price) is included in the Living Wage calculation. The apartment should be in an average urban area, outside the city centre and not centrally located or up-market.

Table 3: List of housing items in the Living Wage data collection

|

How much is the monthly housing cost for a standard apartment suitable for one person (studio or one-bedroom) in your city/region? |

| How much is the monthly housing cost of a standard 2-bedroom apartment in your city/region? |

| How much is the monthly housing cost for a single room in the shared apartment in your city/region? |

| Are these costs included in the rent? |

| Rent (applies to tenants only) |

| Mortgage payments (applies to owners only) |

| Energy - for heating/cooling, cooking, lights, etc. |

| Water |

| Garbage collection |

| Routine maintenance and repairs |

| Taxes on the dwelling |

| Internet connection |

Source: WageIndicator Cost-of-Living survey 2024

If the housing in a region consists of predominantly rural dwellings, the housing costs reflect the prices of such houses. If the region is predominantly characterised by urban apartments, the housing costs reflect the prices of such apartments. This allows comparability of rent both across different countries and across different regions within countries as well.

Utilities are an essential part of the items in the Living Wage data collection. For each housing type, it is defined what is included and what is not included in the cost of housing, as seen in table 4. To view the latest updates regarding utilities in the survey, view Annex 2.

Table 4. List of utilities in the Living Wage data collection

|

Monthly energy cost, including: electricity, gas (heating and cooking), heating and/or cooling, and other utilities used at home |

| Water cost per month |

| Garbage collection cost per month |

| Other monthly costs associated with your house, such as: service/maintenance costs, taxes for dwelling, or city/region specific costs |

Source: WageIndicator Cost-of-Living survey 2024

Transportation is an important cost for households as most people commute for work and daily activities. The Living Wage assumes the use of public passenger transportation (bus, tram, train, shared taxi or local form of transport) provided in most areas. Transportation expenses thus consist of the expenses for a monthly pass (for a full time workweek) for the use of public passenger transportation in most places, thereby assuming that each household member must be able to buy such a card. In areas where monthly passes do not exist, the price of a one-way ticket to the nearest town in local transport is converted to a monthly amount. WageIndicator does not include transport cost for children in the Living Wage If transportation for the children is relevant, for example for the costs of the school bus, it is included in the education cost.

Since 2014, WageIndicator has assumed that families use public transport (bus, tram, train, shared taxi or local form of transport). Over time, WageIndicator realised that in some areas of the world people need a car or a motorbike to move around. Therefore, we included in the Cost-of-Living survey a question to understand the situation in each region.

The question is: "When you go to work, you primarily use:

a. public transport, b. taxi (car), c. mototaxi/rickshaw, d. own car, e. own motorbike/moped/scooter, f. own bicycle, g. I go by foot".

Transport costs related to the job, for example for a taxi driver or rider, are collected within a special section of the Cost-of-Living survey, called “Work-related items”. These prices are used to calculate Living Tariffs for platform workers in specific occupations.

💡Good to know: From October 2024 onwards, WageIndicator has started calculating the cost of a private car as an add-on component in its data (not included in the basic Living Wage) for all countries and regions.

The monthly expenditure on drinking water for a family is collected in the Cost-of-Living survey. This is the cost for bottled water in areas where drinking water from the tap is not possible. This cost is then scaled as per the needs of a family and added as a separate component to the Living Wage. The water cost that is collected in the Utilities section only includes water from the tap, which can be used for washing, cooking, showering and - where possible - drinking.

Having a mobile phone and having data to call and use the internet is nowadays the norm across the world, and hence it is important to include phone and internet expenses in the calculation. The WageIndicator Living Wage includes the cost of a monthly mobile data plan providing at least 120 minutes calls and 10GB internet. Although the price of a phone is collected in the survey, it is for now only used to calculate work related costs for platform workers.

Clothing is part of the essential basic needs. The Living Wage data collection therefore collects information about monthly expenditure for a family of four on clothing and shoes. These expenses are proportionally adjusted for family size. Thus, clothing expenses for an individual are assumed to be one quarter of the expenses reported for a standard family with two adults and two children. In this case, WageIndicator realises that baby clothes might be slightly cheaper, but clothes for teenagers are the same price as for adults (or sometimes even more expensive). These differences are not controlled for in the Living Wage calculation.

The Living Wage data collection includes the basic personal and health care expenses (personal care products and small pharmaceuticals) for a family of four. These expenses are proportionally adjusted for family size. Thus, health expenses for an individual are assumed to be one quarter of the expenses reported for a standard family with two adults and two children.

Next to that, the survey also collects data more specifically on the presence of some form of free or universal public healthcare system in the country and on the cost for a basic health insurance, covering one person and/or one person and the family, and the cost of out-of-pocket expenses. The monthly expenditure for period products and birth-control products, and the prices of personal care products and household cleaning products are also collected. The latest updates to data collection for personal and healthcare items can be found in Annex 2.

Table 5. Personal and healthcare items in the Living Wage data collection

|

Is there some form of free or universal healthcare system in your country? |

| Please provide the monthly cost of the average healthcare costs covering one person, this may include: insurance costs and out of pocket expenses |

| Please provide the monthly cost of the average healthcare costs covering a family, this may include: insurance costs and out of pocket expenses |

| Period products (pads, sanitary napkins, tampons, period panties, etc), per month |

| Birth-control products (condom, pill, patch, etc.), per month |

| Toothpaste |

| Toothbrush |

| Soap |

| Shampoo |

| Moisturizer |

| Toilet paper |

| Hand wash |

| Body wash |

| Cotton swabs |

| Shaving cream/foam |

| Razor |

| Laundry detergent |

| Household cleaning product |

| Dishwashing detergent |

| Sweeper |

| Sponge |

Source: WageIndicator Cost-of-Living survey 2024

💡Good to know: At the 2024 release of Living Wages, the following countries have some form of Free or Universal Healthcare system. This means that either everyone, or specific groups within society (such as babies and pregnant women) are covered universally. These countries include: Armenia, Bangladesh, Belgium, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, China, Colombia, Congo, Dem. Rep., Congo, Rep., Costa Rica, Côte d'Ivoire, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Fiji, France, Gambia, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Guinea, Honduras, India, Japan, Kenya, Lebanon, Liberia, Mali, Nepal, Netherlands, Niger, Nigeria, Panama, Paraguay, Romania, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sudan, Suriname, Switzerland, Tanzania, Togo, Vietnam, Yemen and Zimbabwe.

In most countries education is provided in public schools at a relatively low cost. However, there are often additional costs related to supplementary expenses like transport to and from schools, meals, books, stationery, etc. The Living Wage data collection therefore includes the minimal monthly expenses on children’s education, assuming children attend public schools. Based on the reported minimal expenses on education, the monthly expenditure on education is included in the Living Wage calculation, controlled for family size. The cost of education for adults is not included. Updates to data collection for education costs can be found in Annex 2.

Because the goods and services vary between countries according to the habits and culture but also over time, it is difficult to exhaustively cover personal needs in all countries. One solution to this problem is to provide for spending on non-specified discretionary purchases.

Many Living Wage data providers make provisions for unexpected events in their calculations. The Living Wage Foundation in the UK includes a 15% margin for unforeseen events. Earlier works by Anker and Anker (2013) maintained a 10% margin. Living Wage for Families Campaign in Canada assumes two weeks income from labour on a yearly basis (i.e. approximately 4% of monthly household expenditure). WageIndicator follows Anker and Anker (2017) and adds 5% margin to the final estimate of the cost of living. This 5% margin is also used for the calculation of the Living Income / Tariff,

WageIndicator’s Living Wage data collection assumes that taxes and contributions to social security are part of the essential basic needs. Therefore, one question addresses the monthly taxes on housing. Additional information about monthly income taxes and contributions to social security are derived from country-level tables of taxes by income brackets and social security brackets.

This chapter details how prices are collected for the categories in the Living Wage calculations, as outlined in the previous chapter. It explains the development of the collection since 2014 as well as an explanation of the geographical granularity of the Living Wage data. It also discusses the data collection methods, details about the data collectors and the quality controls during the data collection.

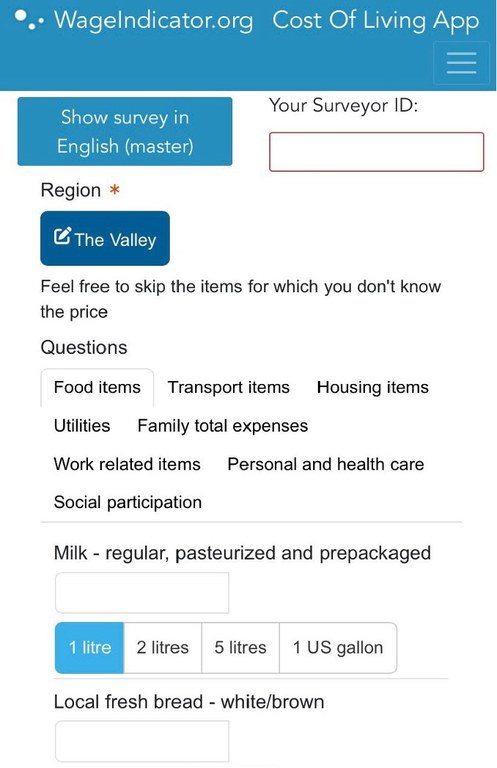

In October 2013, WageIndicator started collecting prices of goods and services. Initially it started with posting teaser on all web pages, asking web visitors for the actual price of a single item. Every day the items in the teaser changed so that after some time all items had been posted (as shown in Image 4, an example from the Paycheck website in India). Web visitors who entered a price were then asked if they were willing to key in the prices of other food items. This was the start of the Cost-of-Living data collection and survey. Items asking about the prices of housing, drinking water, transport, and clothing were added (Guzi, Kahanec, & Kabina, 2016). In 2024, such data comprises less than 5% of all data collected. The primary mode of data collection happens through trained data collectors.

Image 4. Daily changing question in the online Cost-of-Living survey

An example of the Indian WageIndicator website Paycheck.in. The green banner is dedicated to the price of butter/ghee in “your area”, followed by a question in which area the web visitor resides.

Source: WageIndicator website PayCheck.in in India 2023

The Cost-of-Living survey is translated into the different languages of the national WageIndicator websites, and then posted on these websites. By 2015, the Cost-of-Living survey was offered in 84 countries. As of 2024, this now extends to 194 countries and 54 languages in 2024 (see Annex 1).

Since its start, the number of items in the Cost-of-Living survey has been stable in terms of items related to Food, Transport, and Housing. In 2021 an extra section ‘Work-related items’ was added for workers in the Gig- and platform industry. In 2023 a section related to Social Participation was added. Additionally, the Personal and Health care section has been improved over time. You can see the latest items updated in the survey in Annex 2.

Over the years the dataset has grown. Table 5 shows that the number of countries with a Living Wages data collection increased from 45 in 2014 to 173 in 2024. In 2019, WageIndicator started quarterly releases. The table below shows the number of countries for the October releases. Image 5 and Annex 6 show these countries.

💡Good to know: WageIndicator’s Living Wage Data collection increased from 45 countries in 2014 to 173 countries in 2024.

Table 6. The number of countries for whom WageIndicator has collected Living Wage data

|

Year

|

2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| Countries | 48 | 57 | 64 | 48 | 75 | 114 | 130 | 142 | 164 | 173 |

Source: WageIndicator Living Wages data collection 2024

Image 5. A map showing countries where data collection takes place as of 2024

Source: WageIndicator Living Wages data collection 2024

💡Good to know: As of 2024, the data collection for only a few countries is financed by projects. The majority of financing comes from data sales (organisations paying for access to WageIndicator’s detailed Living Wage datasets) as well as from certain companies (like IKEA, Kering, L’Oreal, Schneider Electric and Unilever) with a keen eye on making Living payments in their supply chain a reality, who have sponsored public access to WageIndicator’s Living Wage estimates.

The very first project which covered cost was the Living Wage Eastern Africa project, which ran from 2012 till 2016. WageIndicator trained 70 shop stewards in price data collection and in a meeting in Ethiopia participants were asked about the costs of living, using a print version of the Cost-of-Living survey (Van Norel, Veldkamp, & Shayo, 2016). For the project Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia (2015-2016) price data was collected using the print survey for nine Asian countries (van Klaveren, 2016). In a project studying the global cut flower industry in the floriculture and agricultural sectors of Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, Colombia, and Ecuador, the gaps existing between statutory minimum wages and/or average wages and living wages turn out to be wide (van Klaveren 2022). Within current projects, we and (trade union) partners we work with, now still use our Living Wage estimates in our work. Yet we are not dependent on project money anymore for the estimation of Living Wages.

💡Good to know: Overall and based on recent data calculated for 2020-2022, gaps between statutory minimum wages and living wages vary between 43 and 493 per cent (van Klaveren & Tijdens, 2022). But there are also countries where the Minimum wages is higher than the Living Wage (typical family lower bound). See our quarterly updated visual for more on this.

It is observed that the prices of consumer goods vary not only across countries but within countries as well. This necessitated greater geographical granulation of Living Wage data collection. Since the early 2000s WageIndicator had developed a database with geographical entries for its Salary Survey and then for other apps and web-tools, such as the Cost-of-Living survey. This so-called ‘Region API’ requires the Cost-of-Living survey respondents to identify their region before reporting prices of goods and services as shown in Image 6.

💡Good to know: API is an abbreviation for Application Programming Interface and is a piece of software that makes a database accessible, in this case a database with the names of regions and cities for countries worldwide.

Image 6. Screenshot of the region question in the Cost-of-Living survey, showing for the USA the list of states̵, and after selecting Georgia, showing the choice of cities in this state

Source: WageIndicator Cost-of-Living survey 2024

The WageIndicator Region API allows data collectors and other users to easily identify where they live or collect data. As of 2024, the Region API covers 236 countries and territories, and specifies provinces/states/counties within these countries, the so-called level 1 regional entities, shown in grey in Image 6. Once a province/state/county is selected, a second level option allows for selecting cities, villages, or rural areas, shown in blue. In some provinces/states/counties the second level does not include all cities, since the list of cities would be too long in a survey. In these cases, only the large cities are listed and for the small cities or villages the choice is offered for selecting ‘A small city (10,000 - 100,000)’ or ‘A village (less than 10,000)’. The label set of the Region API is downloadable (see Annex 1).

In 2021, WageIndicator started a process to make sure that all names of all provinces/states/counties in the Region API reflect the most recent administrative divisions and could be mapped in common data visualisation programs like Google Data Studio and Tableau. As of October 2024 this process is about 70% complete.

The Region API allows for a high degree of geographical granularity. Calculating Living Wages assumes enough price observations in each area. Therefore, the most applied granularity is at the first level of the Region API, hence for provinces/states/counties. If the number of price observations at this level are not sufficient, the provinces/states/counties are clustered into four groups, the so-called “Region” cluster groups 1 to 4. A cluster is a group of provinces which are aggregated according to the size of the population of the largest city in the province.

The geographical granularity of the Living Wage data of course depends on the resources to collect the data of prices as discussed in Chapter 2. Over the years, WageIndicator succeeded in collecting more price data and therefore could provide Living Wages for more provinces/states/counties. In case of small countries or in case of insufficient data points, the Living Wages are presented for the entire country only

💡Good to know: As of 2024, WageIndicator provides national and regional Living wages for 173 countries and 2,738 regions. For 252 regions, WageIndicator can present urban data, peri-urban data for 1,141 regions, rural data for 1,530 regions, and super-rural data for 287 regions.

Since October 2023, WageIndicator has also aimed to differentiate Living Wage estimates along urban and rural lines, by identifying four levels: urban, peri urban, rural and super rural. Nevertheless, the urban / rural data and of city level data is not yet meant for guaranteed implementation year-on-year, since this type of granularity cannot be guaranteed each quarter and each year for all regions - for financial reasons. It does help to understand the estimate better. City level and super rural estimates can be provided on demand.

As detailed in Chapter 1, a Living Wage must be an income necessary to provide workers and their families with the basic necessities of life. For the Cost-of-Living survey this implies that prices are collected from shops and markets in low to lower-middle income areas, including housing prices and utilities of these areas. Data collectors are trained in how to collect prices at the cheapest supermarkets or open day markets.

When collecting prices from webshops they are told to avoid webshops where prices are in US Dollars (unless it is in countries where the USD is the national currency). Webshops in US Dollars generally target expats, who usually can spend more. Some food items in the Cost-of-Living survey explicitly refer to a basic quality, thereby excluding luxurious items.

Regarding housing prices, prices given by Airbnb, Booking.com or any other hotel site are not acceptable. Data collectors are trained to research and understand to what extent the housing market is online or offline in the country and adapt the data collection accordingly. They are trained to avoid expensive rental websites in regions where houses are rented through local house brokers or available through housing subsidy schemes (for poorer regions). If the rent is given on a weekly basis, data collectors will convert it for a month as required in the survey. In case of face-to-face surveys (through which data is collected in half of the countries in our database) they collect data and interview people in low- and low-middle class areas where workers live.

The Cost-of-Living data collection takes place through the following five means:

- The Cost-of-Living survey app, used for face-to-face data collection through interviews

- The Cost-of-Living survey app, used to note prices in markets and shops either online or offline

- The Cost-of-Living paper and pencil survey, used when the survey app cannot be used for any reason

- The Cost-of-Living web survey, accessible on national WageIndicator websites

- Data from external sources

Cost-of-Living data collection has been a web-based operation since its inception, with centralised data storage. An app was developed in the late 2010s that allowed data collectors to work offline and archive the data once they have internet access. Data can be entered into the app from any place in the world.

By October 2024, in 90 out of 173 countries Cost-of-Living data was collected face-to-face. Online data collection took place in 30 countries, with hybrid data collection in others. Part of the face-to-face data collection is done through paper surveys, while the rest happens directly through the app on cell phones or tablets. The survey questions are identical across all mediums. Survey data can use the app even when offline and upload the data later, which is important in areas where the internet is not always available or is expensive. The app also allows for data collection in all countries and languages in one place.

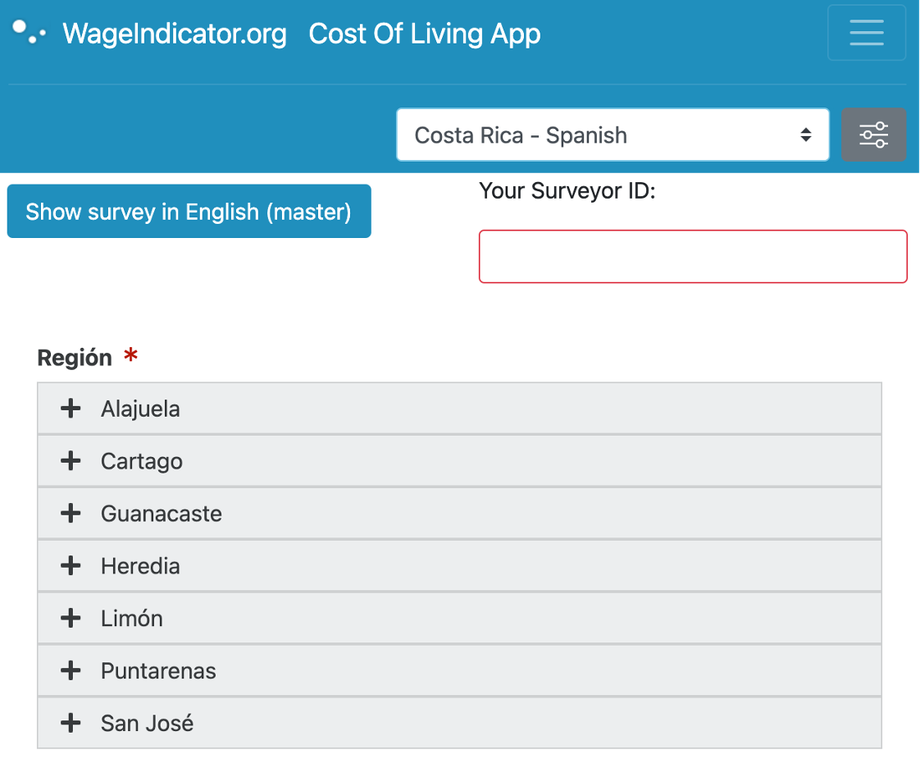

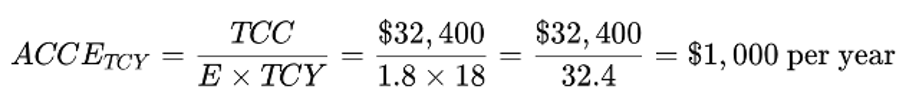

💡Good to know: The Cost-of-Living survey app can be answered in local languages and English [master]. Such as for example in Costa Rica where the survey is shown in Spanish and English, as Image 7 shows. The app has options for 194 countries and 54 languages. The app requires data collectors to identify the country for which the data is collected. By doing so, the currency and the regions are aligned for this country. However, some countries use multiple currencies and in these countries the app allows users to select the relevant currency of the prices. In Zimbabwe, US Dollar, South African Rand and the Zimbabwean Dollar are the options. In Lebanon, Lebanese Pound and US Dollar are the options.

💡Good to know: To make sure that only trained WageIndicator data collectors can access the app, the app requires a 15-digit code called the ‘Surveyor ID’. Every quarter, all data collectors get a new code. The code and the data collectors are linked as such that it becomes visible in the dataset which data collector entered which data and when. This is good both for the data collector as the WageIndicator team can directly support in case of any issues, and fit can be used for quality and assurance checks.

Image 7. Selection of country and region

This screenshot from the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living app shows how a country and language can be selected. In the case of Costa Rica the survey can be done in Spanish and English. Data is always collected country / region specific.

Source: WageIndicator Cost-of-Living survey 2023

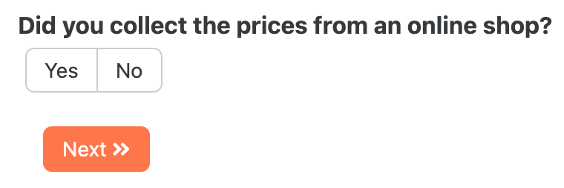

💡Good to know: Webshops - simple and complex - have become commonly used by many people for their daily needs, offering a new avenue for data collection. To accommodate this, the Cost-of-Living survey app now asks data collectors whether they accessed a webshop to collect price data, as Image 8 shows.

Image 8. Extra question at the in the Cost-of-Living survey

Source: WageIndicator Cost-of-Living survey 2023

💡Good to know: During the COVID-19 pandemic, face-to-face surveys proved challenging, so price data was collected partly based through the cheapest webshops. If no suitable webshops were found, face-to-face data collection was done where possible after double-checking with local contacts (Korde et al., 2021).

Whereas shops and markets provide price data for just one locality, webshops can typically set prices for larger areas, ranging from a city to a province or even an entire country. Webshops are classified according to all provinces they serve, and the prices collected from the webshop apply to these regions.

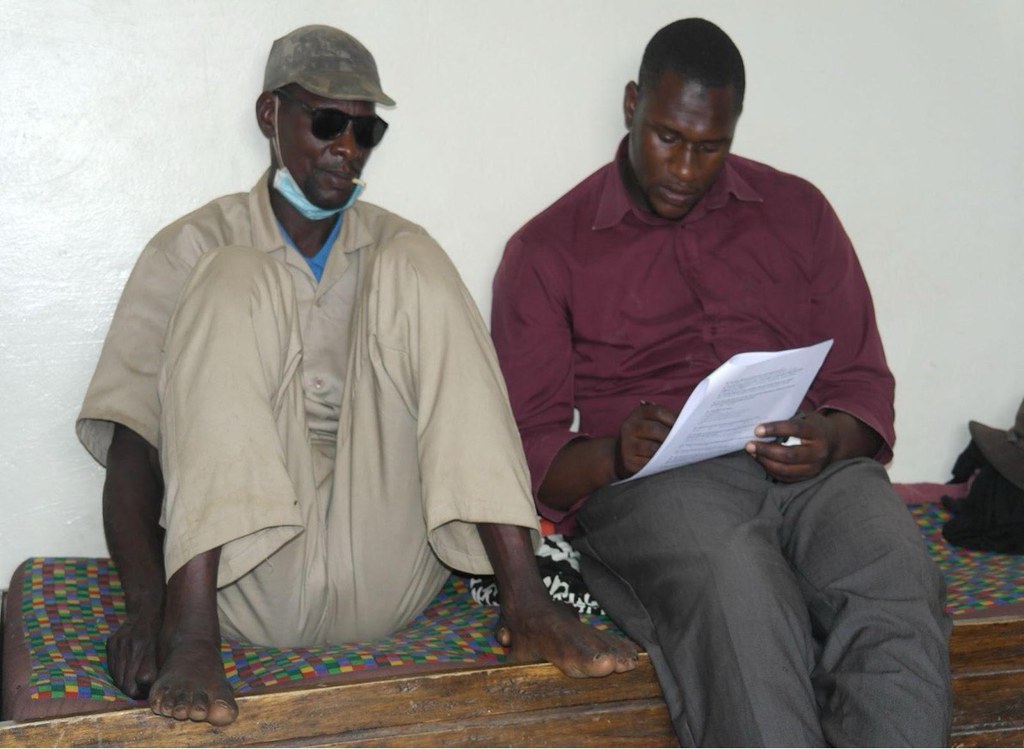

In recent years, some data collectors have found it easier to use printed versions of the surveys, as shown in Image 9. This however does require the results to be entered into the app afterwards, and increases the risk of data entry errors. Some data collectors find it useful to collect data by means of photos of food prices they take at markets or shops, keying in the prices later.

Image 9. Data collection in Richard Toll, Senegal

Source: WageIndicator Foundation, Ⓒ Paulien Osse 2023

The Cost-of-Living web survey is posted on all national WageIndicator websites, as shown in section 3.1. Every day, a different question is posted to each web page of a national WageIndicator website, requesting web visitors to enter the price of one food item. Though this is how data collection began, now only 5% of the data comes in through the websites.

WageIndicator complements its Living Wage data collection with data from external sources. External data sources are:

- World Food Programme’s Global Food Prices Database (WFP Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping (VAM), 2023) for data on food prices

- Numbeo data for prices regarding housing (0 country, from January 2025), as well as some food data.

- Data from national statistical agencies for information regarding health cost, phone cost, and education cost.

All data from various sources are properly checked and outliers are removed. Prices are then incorporated into a comprehensive price database, comprising over 9 million of price points, that is used for living wage calculation.

Data collectors are critical for the success of the collection of prices. WageIndicator employs data collectors with a background in survey research, data collection and statistics. As the number of countries for whom Living Wage calculations has grown over time, so have the number of data collectors. They are organised in teams covering regions within countries, regions, language groups, parts of continents, with one or more team managers. Across the world and on most continents, data collection is done face-to-face. For a few countries in Europe and North America, data collection is hybrid or online.

Managers oversee the data collection processes, train the data collectors, and provide feedback. Groups are trained together in webinars and special sessions are organised to answer any queries they may have. The data collectors collect price data from local citizens, open markets, supermarkets. Some data collectors work directly under global managers of data collection, others work under supervision of regional operating agencies.

The efforts of all local data collectors are complemented by interns. All interns are screened before selection. The interns work for a minimum of two months full-time, but usually it is 6-9 months part-time. Interns always work under supervision of global data collection managers.

Table 7. Characteristics of the data collectors in 2024

|

|

Persons* | Regions | Training | Experience | |

| 1 | Interns during one year | approx. 120 interns | Usually countries where English is the main language | 2 hours training, and weekly update of 20 minutes | Minimum 2 months |

| 2 | WageIndicator team members during one year | approx 220 team members; they are specialised data collectors, work on year contracts * | Most countries in the world. Especially in countries where online supermarkets or other data is not always available or up to date. | Written instructions, instruction videos, and quarterly feedback quality updates | From 2 till 6 years |

| 3 | Web users WageIndicator national websites | 9,726 users in 2021, 4,752 users in 2022 and 2,665 users in 2023 ( 1 price per user) | Medium/high income countries | No training | Unknown |

Source: WageIndicator Foundation 2024

In 2024, interns came from FLAME University, University of Kassel, Berlin University, University of Amsterdam, Bucharest University, Shiv Nadar University, St. Xaviers College, New York University Abu Dhabi, University of the Witwatersrand, University of Cape Town, University of Queensland, Eduardo Mondlane University and University of Ahmedabad.

WageIndicator provides online training via Zoom, WhatsApp or their preferred (and safest) means of communication, in written instructions, instruction videos, and quarterly feedback quality updates. Trainers are global and regional WageIndicator managers. Global managers oversee the whole process of recruiting data collectors, assigning jobs to data collectors, calculation, and use of the data by companies, NGOs and trade unions. Regional data managers oversee the process of assigning jobs to data collectors and have insight in the quality of the work done by data collectors.

The data collectors correspond regularly with their team managers or directly with their global managers, confirming that the information they are collecting is valid. Table 6 provides an overview of the training provided.

💡Good to know: All data collectors and their team managers get the same instructions and training, whether it is for collecting data from webshops, or face-to-face and then keying in the data in the Cost-of-Living survey app. The training usually takes 90-120 minutes. Data collectors take a refresher training every year, where feedback on data collection and on the survey is also taken into account.

Trainings for data collectors focus on the following issues:

- To use the survey

- To upload stored data

- How to select appropriate areas for data collection, in terms of costs

- To avoid the poorest and richest areas, where possible

- To go to areas where workers live, not the tourist or expat area

- Select respondents randomly

- To take time to talk to respondents while following the survey

- To collect food prices at the market/shops randomly

- To collect housing prices regarding decent housing (safe, solid roof, water, electricity, heating, sanitary toilet facilities)

Data collectors should be:

- Accurate and precise

- Good with numbers

- Able to communicate with people on equal level

- Multilingual

- Able to use a smartphone or digital device

WageIndicator has learned some useful practices through years of data collection:

- Sometimes it is better not to use a smartphone, but a printed survey

- Interviewing in pairs is sometimes more efficient, faster and safer than doing it alone.

- Some countries report that women are better trained to talk about prices with women, men are better at talking about prices with men. Nevertheless mixed-gender teams seem to be the best

- Data collectors usually know that the price is collected to calculate Living Wages, yet data collectors are trained not to tell their respondents that the prices are collected to calculate Living Wages

- Data collectors never know which companies might use the Living Wage estimates

- If extra data is needed for a client of WageIndicator, the name of the client is not shared with neither the trainer, the data collector nor the respondent.

- If needed for authorities or safety purposes, data collectors are provided with a WageIndicator introduction letter or other safety measures are taken.

On a daily basis the WageIndicator team managers check the data collected. Specifically, the housing prices are cross checked across the different surveyor groups operating simultaneously (Korde et al., 2021).

All data collectors have a unique code related to their name and email address which they must use to collect their data. Each price in the database can be traced back to an individual data collector. However, the code is not required for web users who key in data on the basis of a request as shown in Image 4. In general, web users key in one price only.

Global data managers, regional data managers and data collectors in the countries are in touch with each other on a daily basis through various instant messaging applications.

All data collectors have undergone WageIndicator’s annual safeguarding training and adhere to WageIndicator’s Code of Conduct.

WageIndicator updates its Living Wage estimates every quarter to keep up with changing price levels. The quality of national and regional Living Wage estimates are rated internally by assigning a Stability and Data Quality Code to each country and region, based on a comparison with the data for the same country/region from the previous quarter. Data fluctuations have been tracked since January 2019.

When a >10% change is observed, a thorough check is conducted to assess whether there is an issue with any of the input components. If such an issue is found, it is corrected in the script and the estimates are recalculated. If no issue is found, the data collector is contacted for an explanation. If even this does not suffice, the estimate is retracted from the database and in the following quarter an additional team is assigned to collect data independently from the existing team. If their results differ, estimates are adjusted as needed and in some cases the team of data collectors might be replaced. Table 8 shows the levels and frequency of quality checks.

Living Wages are checked for consistency over time. In case structural discrepancies are detected, WageIndicator consults national experts to analyse and correct the source(s) of bias. These experts are mainly academics from the WageIndicator network. Next to that WageIndicator gains expertise from multinational clients by talking to their local HR teams. In case of issues, WageIndicator brings HR experts from different clients together and discusses the topic. Thanks to these efforts, the data also becomes more accurate over time.

Feedback on methodological questions and the quality of Living Wages is also obtained through discussions in webinars (see Annex 4) involving academics, employers, trade unions and data collectors. All relevant feedback can be integrated in the survey over several quarters. One example of this is a change of wording because of a “wrong” translation, but also the integration of extra questions in the Cost-of-Living survey related to social participation. This specific component of social participation has not been finalised yet. Decisions on this will be made in Q1 2025.

Table 8. Levels and frequency of quality checks

|

Quality checks |

Yearly | Quarterly | Daily |

| Survey | |||

| Survey correct - does it produce the correct data from the correct country / region | x | ||

| Survey correct - new countries / item language / translation checks | x | x | |

| Survey - region / city - correct | x | x | |

| Survey items still relevant | x | ||

| Data collection | |||

| Data collectors - recruiting / screening | x | ||

| Interns - recruiting / screening | x | ||

| Data collectors training | x | ||

| Interns training | x | x | |

| Offer option to data collectors to report in case they included mistakes | x | x | |

| Assign extra data collectors - they don't know each other - in one country. (f.e. face to face and online) | x | x | |

| Data process | |||

| Check for outliers (not above or below a defined number) | x | ||

| Check for currency mistakes | x | ||

| Check for currency mistakes in case of more currency options (Lebanon, Venezuela, Zimbabwe) | x | ||

| Check for consistency between quarters | x | ||

| Check for relation with World Food Programme database | x | ||

| Check for relation with Numbeo housing data | x | ||

| Check for the consistency between the components | x | ||

| Check the relation between housing and Minimum Wages | x | ||

| Check for tax and social security updates | x | x | |

| Update for inflation twice a year | x | ||

| Feedback | |||

| Feedback during data collections process | x | x | |

| Feedback on the basis of estimates by all data collectors | x | ||

| Feedback from clients on the basis of estimates | x | ||

| Double check | |||

| Calculations of family-types | x | ||

| Year averages | x | ||

| Comparison quarters / stability over quarters | x | ||

| Include Living Wage/Income Guidance data set | x | ||

| Minimum Wages | x | ||

| Check requests from clients (MNE / NGO / Trade Union / web users) | x | x |

Source: WageIndicator Living Wage Data Collection 2024

This section details WageIndicator’s data collection strategies to avoid bias in the samples:

- For the data collection of prices from shops/markets, the sampling frame consists of shops/markets located in low-income areas, because the Living Wage data collection aims at the lowest prices for the defined food basket. The shops/markets are sampled by random walks in these areas. WageIndicator data collectors go to these shops/markets and register the prices, similar to what mystery shoppers in retail establishments do. This data is collected by WageIndicator data collectors using the Cost-of-Living app.

- For the data collection of prices from webshops, the sampling frame consists of all webshops that can be found online in the selected region/city, and the sample consists of the webshops with the lowest prices for the selected food basket; this data is collected by WageIndicator data collectors using the Cost-of-Living app.

- For the data collection of housing prices from the respondents responding on behalf of their households, respondents’ locations are selected in low, low-middle income areas, and real estate agents may also be consulted.

- For the data collection of housing prices from real estate agents, the low, low-middle-income areas are selected and various real estate agents are visited;

- For the data collection of prices from web visitors of the more than 200 national WageIndicator websites on work and wages, the Cost-of-Living web survey in their national languages is used. Here no sampling frame exists as the data collection is based on a non-probability web survey.

- For the data collection of food and housing prices, data from external sources are added, when available and when assessed to be reliable.

- An alternative strategy of collecting price data is by means of household expenditure surveys. These surveys primarily aim to measure expenditures, but they are also used to generate data on prices. However, the price data from expenditure surveys are often less granular compared to the price data collected from shops, markets and other outlets, and they most likely rely on respondents' memory, hence less reliable. Whereas WageIndicator’s Living Wage data collection targets low-income strata of cities and villages, expenditure surveys mostly aim to sample the full population of households. To meet the demands of data collection of prices in low-income areas, usually a subsection of the sample, large sample sizes are needed. Instead, WageIndicator prefers to focus on data collection in shops and other outlets.

Measurement errors are likely to be small as the prices are directly observed by the data collectors. When prices are collected from volunteer web visitors, they are not urged to report the lowest prices but to report the prices they paid today or yesterday. The latter price data collection can be prone to selection bias. WageIndicator assesses the possible bias of this data in the total sample as small, because the large majority of data is collected by trained data collectors.

💡Good to know: What happens if data collectors key in wrong numbers? WageIndicator applies a strict regime to control for data-entry errors. Statistical methods are applied to identify data-collector related outliers, as well as outliers when comparing to previously collected data.

There are clear thresholds on the minimum number of prices collected per region/country per component.

- For food there should be between 2000 and 6000 prices per region; if less data is available, there will not be a Living Wage estimate for that quarter.

- For housing between 50 and 200 observations are needed to calculate housing for a country-level and 20 and 200 observations for a region-level Living Wage.

- For transport a minimum of 20 observations are needed for country-level estimates and 20 observations for region-level estimates.

- 20 observations are needed to calculate on national and regional level for health, education, clothing/footwear, phone and drinking water expenses.

💡Good to know: If there are not enough observations at the regional level, the national data is used also for the region-level Living Wages, as these are smaller expenses and usually don’t vary too much per region. If there are not enough observations at the national level (for health, education, clothing/footwear, phone and drinking water expenses), data from countries within the same income group (as per the World Bank country income grouping) are used by comparing the ratio of the components to a set of minimum wage levels set by the ILO and from WageIndicator’s Minimum Wage database.

This chapter focuses on the calculation of the Living Wage, and the related estimates for a Living Income and Living Tariff. It details the data streams in the Living Wage data, the assumptions underlying the Living Wage calculations, the components of the Living Wage calculations, and the features of the Living Wage dataset.